Clara Vilaboa on her PhD project

Comics have consistently been associated with childhood and the child reader. Over the past decade, children’s comics have started receiving more attention from teachers, literary mediators and researchers (Tarbox, 2020). In the Spanish context, comics (including tebeos, comic magazines, comic strips, etc.) have had a significant effect on the children’s interest in reading, the development of their reading skills and their understanding of the world (e.g. Agüero, 2022; Ibarra-Rius & Ballester-Roca, 2022; Van de Wiele, 2022).

Elementary schools have collected comics in their libraries and classrooms for a long time, and comics have played a key role in the reading experience of several generations of children and adolescents (Ballester-Roca & Ibarra-Rius, 2019). It was not until recently, though, that the status of comics shifted from non-canonical to legitimate school reading, and that teachers and librarians began to actively promote comics in the school. Considering the literary and pedagogical value of comics, elementary educators have identified comics as key narrative forms for strengthening children’s literary education through the development of multimodal reading competence and the promotion of contemporary key skills (interculturality, critical thinking, etc.). Although this deliberate and structured integration of comics in schools is relatively recent, there are various studies that propose, document and analyse the use of comics and graphic novels for children in elementary school (e.g. Brenna, 2012; Chase, Son & Steiner, 2014; Dallacqua, 2019; Cabarcas, 2020; Pantaleo, 2020).

Framed in this intersection between comics and education studies, the project Comics and graphic novels in the literary education of the child reader, at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, takes on a holistic approach to interpret the reality of comics as part of the reading ecosystem of the school, including different contexts (like the classroom, the library and the halls) and agents (such as the child as a reader, the adult as a teacher and the librarian as a mediator). To do so, an ethnographic, collaborative and longitudinal study has been carried out in a public elementary school in Barcelona (Spain), from which I will address the comic collection in the school library and the interaction of the child reader with this collection.

We have worked with three different corpora of comics: the school library collection, a temporary loan from the public library and a small collection of comics that have been used for classroom workshops. Focusing on the library collection, we can find two sub-collections separated by the research intervention: the existing and updated collections.

We initially identified 132 comics scattered in the school and classroom libraries. The majority of the collection consisted of children’s comics with what can be considered Franco-Belgian and Spanish classic comics, such as The adventures of Asterix, The adventures of Tintin, The Smurfs or Mortadelo y Filemón. There was also a noteworthy collection of the Catalan comic magazine Cavall Fort, as well as a small collection of children’s graphic novels, such as the Catalan Agus & Monsters or Bitmax & Co. When we discussed this collection, the interviewed teachers and librarian highlighted the need of updating it to include comics which are more appealing for the readers based on their aesthetics, themes and characters. For instance, a teacher pointed out that, often, readers in her classroom would not be as interested in comics as in other books because of the small text and less colourful illustrations that characterised the comics in the library. Likewise, the librarian pointed to the gender stereotypes in some of the comics and how these comics needed to be addressed by the teachers and reviewed as part of the school collection.

Part of the initial comic collection

Considering the perspectives and needs that arose regarding the comic collection, we designed, between teachers, researchers, families and a bookseller, a collection update based on the following criteria: the promotion of the lingua franca of the school (Catalan), the variety of themes for different interests and ages (from 3 to 12), the quality of the multimodal narration (text and images), and the adequateness of the ideas and themes (gender roles, social stereotypes, etc.). Following these criteria, the school acquired 39 new comics as a first contribution to the collection that will be enlarged in the future based on feedback from the students and teachers.

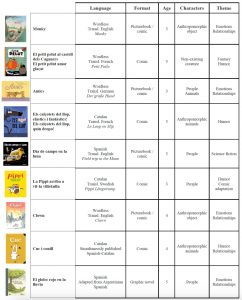

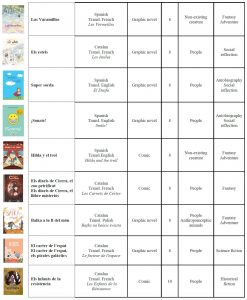

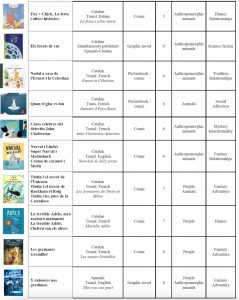

The update included a variety of comics and graphic novels for the child reader, which we have classified according to the language, format, theme and recommended age (see the Updated collection chart). Building on the analysis that Colomer (1998) and Medina (2019) make regarding common trends in children’s literature, we can reflect on the characteristics of the comics that were integrated into this elementary school. While we cannot define each reader’s preferences and these categories are based on recommended ages for the comics, there are perceivable trends influenced by the readers’ age and the reading skills and interests often associated with the age.

Part of the update of the comic collection

Literature for early readers tends to accord great importance to the image and to meaning-making through visuals. Likewise, comics for first readers in this collection (3-5 year-olds) highly rely on visual narration, using short sentences and dialogues, or being often wordless. The iconic language is used to connect the readers to topics that are familiar or relevant to them, such as emotions and relationships (friendship and family). This is also done by presenting humorous and fantastic narrations that bring them closer to these topics by appealing to their imagination and playful attitude, often portraying characters who are anthropomorphic animals or animate objects that appeal to this imagination. These comics tend to play with format and mix it with that of picturebooks. As Gibson (2010) and Tarbox (2020) reflect, picturebooks and comics are flexible media that share many iconic-textual aspects and hybrid comic-picturebooks for young readers incorporate elements from both formats, as in the case of Monky, Clown or Amics.

In the comics addressed to readers in motion (“lectores en marcha”, 6-8 year-olds) we can see a bigger range of topics and genres, focusing mainly on fantasy but also including mystery, social reflection, information, traditional folklore and humor. Some comics start introducing complex topics, such as Els forats de cuc (the concept of black holes), and more complicated narrative structures and resources, as Casos celebres del detectiu John Chatterton (meta-fictional references). In these books, there is a balance between human and anthropomorphic animal characters – it is interesting to consider the case of Quan el glaç es fon, in which the main character is a polar bear and does not act like a human being. This enhances the realistic character of a comic that aims to spark a conversation about climate change, a hint to the beginning of an interest of the readers in social and real-life narratives. Concerning the format, comic series are popular for this group of readers because of their appeal to the readers’ interest in following a story through time but at a pace fragmented in volumes, which is therefore not too overwhelming.

Comics for autonomous readers (8-12 year-olds) cover all kinds of topics and themes. It is interesting to highlight the balance between fiction and realism since comics for this age range tend to introduce more realistic stories as readers become more interested in exploring their own and others’ realities. This is approached both through fantastic narrative and realist fiction. The interest in relatable stories is reflected in the predominant character type since most of the protagonists are people – at this age, readers tend to look for stories with characters that they can relate to, such as those in Smile! and El Deafo, or that go through a series of extraordinary events and adventures that are fascinating for them, as in This was our pact and Baika a la fi del món. In this case, the collection is dominated by graphic novels, which implies an interest of the readers in comic books that allow them to explore extensive and conclusive stories.

In general, this brief analysis of the collection reflects that comics for children are highly diverse in their stories, tend to experiment with formats and often present stories that aim to achieve a variety of functions, such as entertainment, learning and discussing. Since these comics are created for child readers, it is essential to consider their perspectives and stances regarding comics.

Various questionnaires, interviews and focus groups with the readers signalled a generally positive attitude towards comics and, in many cases, a preference for reading comics, graphic novels and manga over other literary texts. Those who considered themselves comic readers or who expressed a reading interest in comics pointed out that the most important aspects that influence this interest are the image (the illustration style, the colours and the line), the plot (regarding the diversity of themes and the “creativity” and “humour” in the comics) and the reading accessibility of the narration (due to a minor presence of text).

Regarding the collection of comics some readers mentioned the lack of comics for different ages and preferences and, in general, all readers expressed interest in increasing the collection with new comics, graphic novels and manga. While the adult mediators gave great importance to the values, topics and themes in the comics, the readers focused mostly on the lack of variety in topics and contemporary comics, leaving aside the values reflected on them. In fact, some referred to their enjoyment when reading comics that could be considered problematic due to their content (i.e. gender stereotypes). One of the older interviewed readers referred to comics in the collection as “too childish” and insisted on the absence of comics for his age and interests, which reinforces the school’s intention of having comics for all readers.

Frequent comic readers expressed a lot of interest in having collections of comics in the school library in order to follow their favourite series or to share these books with their peers in the school. In contrast, those who preferred text-only narratives (mainly novels) often mentioned that, if they were to read a comic book, they would prefer graphic novels as they were interested in extensive, conclusive stories. Additionally, some of the interviewed readers talked about the importance they accord to re-reading books and how having the opportunity to read comics in school more than once was valuable in learning to appreciate the visual details and meanings in the narrative. In general, the readers were eager to engage with the comics, which is something that both the librarian and the teachers reported since readers were continuously asking about the new comic collection in the classrooms and in the library.

Throughout this project, we have been able to document how teachers and other mediators are working to integrate comics into the school practice in a way that considers the readers’ needs and current interest in this narrative. Likewise, it has been an opportunity to document how readers actively enjoy these multimodal narrations that appeal to their interest in highly visual, complex and compelling stories regardless of their age.

As mentioned previously, comics have been studied from different educational perspectives (for instance, for multimodal creation or interdisciplinary learning) but there is a current need for more research focused on reading comics in the school (Kirtley, Garcia & Carlson, 2020). However, there is copious research on the importance of reading multimodal narratives in the classroom and their significance for developing critical, multicultural and multimodal reading literacies (e.g. Amat, 2010; Farrell, Arizpe & McAdam, 2010; Colomer, 2012). Furthermore, one of the aspects highlighted by this research has been the relevance of studying the different agents and spaces that take part in this process. In this sense, this case study illustrates a key condition for integrating comics as part of literary education in schools: it is important to update the comic collection but it is not enough unless we carry out actions that actively promote and give value to comics, putting the voices of the teachers, librarians and child readers at the centre of the educational innovation.

A table of the comics collection by Clara Vilaboa

References

Agüero Guerra, M. (2022). Representaciones de la infancia en el cómic: de la nostalgia al compromiso social. León: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de León.

Amat, V. (2010). Compartir per construir: Aprendre a valorar àlbums a cicle inicial. Narratives gràfiques, 52, 32-41.

Brenna, B. (2012). How graphic novels support reading comprehension strategy development in children. Literacy, 47(2), 88-94. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4369.2011.00655.x

Cabarcas Morales, Y. (2020). El cómic en el aula: una didáctica narrativa. Educación y ciudad, 38, 125-134. https://doi.org/10.36737/01230425.n38.2020.2325

Chase, M., Son, E. H., & Steiner, S. (2014). Sequencing and graphic novels with Primary Grade students. The Reading Teacher, 67(6), 435-443. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1242

Colomer, T. (1998). La formació del lector literari. Barcelona: Editorial Barcanova.

Colomer, T. (2012). Las discusiones infantiles sobre álbumes ilustrados. In Colomer, T., & Fittipaldi, M. (Eds.) La literatura que acoge: Inmigración y lectura de álbumes (pp. 87-118). Caracas: Banco del Libro.

Dallacqua, A. K. (2019). Reading Comics Collaboratively and Challenging Literacy Norms. Literacy Research and Instruction, 59(2), 169-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2019.1669746

Farrell, M., Arizpe, E., & McAdam, J. (2010). Journeys across visual border : annotated spreads of “The Arrival” by Shaun Tan as a method for understanding pupils’ creation of meaning through visual images. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 33(3), 198-210. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03651835

Gibson, M. (2010). Picturebooks, comics and graphic novels. In Rudd, D. (Ed) The Routledge Companion to Children’s Literature (pp. 100-111). Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis Group.

Ibarra-Rius, N. & Ballester-Roca, J. (2022). El cómic desde la educación lectora: confluencias, interrogantes y desafíos para la investigación. OCNOS: Revista de estudios sobre lectura, 21(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.18239/ocnos_2022.21.1.2753

Kirtley, S. E., García, A., & Carlson, P. E. (2020). With great power comes great pedagogy. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Medina, M. B. (2019). La Literatura Infantil y Juvenil Iberoamericana: Un mapa de tendencias. En Anuario Iberoamericano sobre el Libro Infantil y Juvenil 2019. Madrid: Fundación SM. Retrieved from https://www.fundacion-sm.org/investigacion/anuario-iberoamericano-sobre-el-libro-infantil-y-juvenil-2019/

Pantaleo, S. (2020). Elementary students meaning-making of the science comic series by First Second. Education 3-13: International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, 49(8), 986-999. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2020.1818268

Tarbox, G. A. (2020). Children’s and young adult comics. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Van de Wiele, E. (2022). Building a glocalised serial for children: Corriere dei Piccoli (1908-1923) and TBO (1917-1932) [PhD thesis, Ghent University]. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-8759231