By Robert Aman (robert.aman@liu.se)

Like elsewhere in Western Europe, the effects of 1968 in Sweden cannot be confined to a specific manifestation or mode, but was a total social phenomenon (Wolin 2010). In addition to studies on the birth of the New Left (Ekelund 2017), student revolts (Bjereld & Demker 2005), solidarity movements (Sellström 1999) and other events associated with the leftist radicalisation of the period, scholarly attention has been steered towards the ways in which aesthetical forms and genres were impacted but was also used to disseminate political doctrines. This includes music, literature, and poetry as well as pop and rock music (e.g. Arvidsson 2008; Kåreland 2009; Svedjedal 2014; Widhe 2018). What these studies show is that a great number of writers used different forms of texts for political opinion formation in order to place society and politics under scrutiny (Svedjedal 2014). Less is known about the role of comics as a medium for exploring questions of social inequality, international solidarity and antiracism, having absorbed the radical politics of New Left social movements. Creators produced plots that, besides aiming to entertain, treated and commented upon contemporary concerns such as the exploitation of the Third World, pollution, and gender equality, and they offered heroes to deal with such problems. In a few cases, the heroes were children (and almost exclusively boys).

Comprising four albums published between 1977 and 1982, written by the Swede Janne Lundström (1941) and drawn by the Catalan Jaime Vallvé (1928-2000), Johan Vilde (translation: John Savage) is a comic that deals with what has been referred to as a concealed part of Swedish history – namely Sweden’s involvement in the slave trade during the seventeenth century (Jonsson 2005). The protagonist, a young Johan Klasson Tay, is a cabin boy on a Swedish merchant ship who is forced to escape after being accused of mutiny. After jumping ship, he floats ashore in Cabo Corso – located in modern-day Ghana – where he encounters the Ayoko clan. Taken to their village, he is eventually adopted by a local family and grows up in an African kingdom. From there, he will go on to witness the harshness and brutality of the slave trade with his own eyes. With the looming threat of being captured by the Swedish slave traders and his family being sent to work on plantations in the Caribbean, the hero Johan Vilde is faced with a new challenge in each album, and must use all his wiles and talent in order to save both himself and his adoptive family from the men of his country of birth. Symptomatic of its publication at a time when Sweden was beginning to position itself as a leading anti-colonial voice, when the first album in the series, Johan Vilde: the Fugitive, was awarded the first prize in the publisher Rabén & Sjögren’s comics competition the jury placed emphasis on the fact that ‘[t]he authors see the ruthless human exploitation from the perspective of the oppressed slaves.’

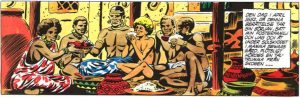

More importantly and in line of the exotic view of the continent that V. Y. Mudimbe (1988) has identified as part of the construction of Africa in western representations, Johan Vilde finds himself in the midst of an African golden age of perfect liberty, equality and fraternity. Or has he concludes himself, I’m in paradise!’ (Aman 2016). Differently put, the Johan Vilde series perpetuates an exotic vision in which the use-value of Africa is as a paradise lost, a utopian future past, a Romantic mirage of a non-capitalist alternative beyond the bounds of modern civilisation. In contrast to the imperialist narrative in which the white man or woman travels to the periphery to report home about places and people he or she encounters, with an emphasis on lack and shortcomings, the periphery is in this case – emblematic of Swedish travel writings during the 1970s – valorised as superior to the materialistic and oppressive centre. The comic book series became so popular that Lundström, on the direct request of his editor, would also go on to publish six novels about Johan Vilde’s continuing adventures on the African continent.

Johan Vilde surrounded by his adopted family. From Johan Vilde: the Fugitive (1977).

Another example from the same period is Mystiska 2:an (The Mysterious 2) which was created in 1969 by writer and artist Rolf Gohs (1933-2020). The main protagonists are Stefan and Sacho, two working class boys in their younger teens. The series is predominately set in a Stockholm undergoing a radical make over. The city functions as a surface, where projects of modernisation such as the public housing programme – Miljonprogrammet – acts as a stage for Stefan and Sacho’s adventures just as often as the older housing stocks awaiting demolishment in rough parts of the city. The theme is familiar from leftist novels of the period that advance stern criticism of the governing Social Democratic party who are blamed for successively dismantling the welfare state. In addition to criticism of commercialism, capitalism and class society (Svedjedal 2014).

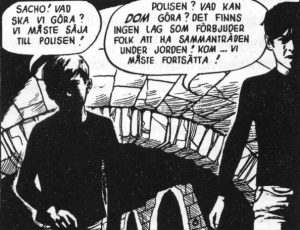

Stefan and Sacho on their way to prevent a planned fascist coup d’état. From Mystiska 2:an: Mysteriet i Rosenkammaren (1970).

In Mystiska 2: an Sacho is the oldest son in an unidentified immigrant family living in a small apartment in a working-class area in central Stockholm; Stefan grows up with his single mother under similar economic conditions in a social housing estate in the outskirts of the city. The villains of the series are predominately unscrupulous multinational companies, drug dealers, authoritarian police officers or parents with similar leanings. But also a fascist organisation hiding in the Old Town, Stockholm’s historical centre, planning a coup d’état. With drawings in black and white full of ink and asymmetrical panels, there is an almost documentary sensibility to the storytelling alluding more to Stefan Jarl and Jan Lindqvist’s influential documentary ‘Dom kallar oss mods’ (They Call Us Misfits) from 1968 than another comic book. As a token of its popularity, Mystiska 2:an was also published in Denmark and Germany, and the socialist leaning pop band, Doktor Kosmos, recorded a song about the comic book. Between 1970 – 1973, Mystiska 2:an had its own monthly comic book and was also published as a daily strip in Expressen and Arbetarbladet. Until 1985 Gohs went on to publish in total 21 full albums about the adventures of Mystiska 2:an.

Johan Vilde and Mystiska 2:an were far from alone in the period to reflect the ideological landscape in Sweden. Other notable examples include the originally American superhero The Phantom who was subjected to a radical makeover in terms of political leanings when a group of Swedish creators started to produce their own manuscripts (Aman 2018a). A potent colonial symbol administrating justice in the African jungle suddenly starts to speak about international solidarity, gender equality and antiracism (Aman 2018b). With the introduction of stories produced out of Stockholm, the comic sold throughout the 1970s an average of 170 000 copies biweekly (Aman 2020). Another example is the series Tumac about a young Inca boy who fights against racial injustices, pollution and multinational companies seeking to exploit natural resources in Latin America. Taken together, the content of these comics seems to have resonated with readers. After all, in a recent edited collection from the Swedish Comics Association on the history of Swedish comics, the ‘progressive 1970s’ is claimed to be the ‘golden age’ of sales. Only during the year of 1979, the total sale figure for comics was 44,7 million in a country of roughly eight million inhabitants (Zetterstrand 2019). Only Donald Duck sold better than The Phantom, and, for example, the first album of Johan Vilde sold 50 000 copies.

References

Aman, R. (2016) Swedish Colonialism, Exotic Africans and Romantic Anti-Capitalism: Notes on the Comic Series Johan Vilde, Third Text, 30(1-2), 60-75

Aman, R. (2018a) When The Phantom Became an Anticolonialist: Socialist Ideology, Swedish Exceptionalism, and the Embodiment of Foreign Policy, Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 9(4), 391-408

Aman, R. (2018b) The Phantom fights Apartheid: New Left Ideology, Solidarity Movements and the Politics of Race, Inks: Journal of the Comics Studies Society, 2(3), 288-311

Aman, R. (2020) The Phantom Comics and the New Left: Socialist Superhero Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Bjereld, U. & Demker, M. (2005) I Vattumannens tid? En bok om 1968 års auktoritetsuppror och dess betydelse i dag (Stockholm: Hjalmarson & Högberg)

Ekelund, A. (2017) Kampen om vetenskapen: Politisk och vetenskaplig formering under den svenska vänsterradikaliseringens era (Göteborg: Daidalos).

Jonsson, S. (2005) Världen i vitögat: tre essäer om västerländsk kultur (Stockholm: Norstedt)

Kårleland, L. (2009) Inga gåbortsföremål. Lekfull litteratur och vidgad kulturdebatt i 1960-och 70-talens Sverige. (Göteborg: Makadam)

Mudimbe, V. Y. (1988) The invention of Africa: gnosis, philosophy, and the order of

knowledge (Bloomington: Indiana University Press)

Svedjedal, J. (2014) Ner med allt?: essäer om protestlitteraturen och demokratin, cirka 1965-1975 (Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand)

Zetterstrand, E. (2019) “Rekordåren”, i: U. Granberg (red.) Svensk seriehistoria: tredje boken från Svenskt seriearkiv. Malmö: Seriefrämjandet.

Widhe, O. (2018). ’Slåss mot alla orättvisor. Katarina Taikon och föreställningen om barnets rättigheter runt 1968’, Barnboken, 41, pp. 1-19.

Wolin, R. (2010) The wind from the east: French intellectuals, the cultural revolution, and the legacy of the 1960s (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press)